User guide¶

Datoviz is a C-first library. It provides auto-generated Python ctypes bindings that closely follow the Datoviz C API.

While this user guide focuses on Python for convenience, it can be readily translated into C.

To use a Datoviz C function in Python, you typically need to replace the dvz_ (functions), DVZ_ (enumerations), or Dvz (structures) prefix with dvz. after importing Datoviz with import datoviz as dvz.

Please note that this user guide is a work in progress. We strongly recommend looking at the examples (located in the examples/ subfolder of the repository) and the auto-generated C API reference (found in docs/api.md).

Overview¶

Creating a GPU-based interactive visualization script with Datoviz in Python typically involves the following steps:

- Creating an

appand ascene. - Creating one or several

figures(window). - Creating one or several

panels(subplots) in each figure, defined by their offset and size in pixels. - Creating

visualsof predefined types. - Setting the visual data (position, size, color, groups...).

- Optionally, setting up event callbacks (mouse, keyboard, timers...).

- Optionally, creating GUIs.

- Running the application.

- Closing and destroying the

sceneandapp.

GPU knowledge is not required when using this interface.

The lower-level GPU-based layers are not yet exposed in the datoviz.h public header file.

Contact us if you would be interested in using them in your application.

App and scene¶

The app handles the window, user events, event loop.

The scene handles the panels, visuals, and data.

A visualization script is typically organized as follows:

# This imports the binary libdatoviz shared library.

import datoviz as dvz

# Create an application. The argument is reserved to optional flags, like dvz.APP_FLAGS_OFFSCREEN

# for running an offscreen application (without a window, saving a figure to a PNG file).

# See the offscreen.py example.

app = dvz.app(0)

# Retrieve the app's batch, which contains a stream of Datoviz Intermediate Protocol requests that

# will be processed at the next frame by the app's event loop. It's used to create visuals.

batch = dvz.app_batch(app)

# Create a scene, which handles the plotting objects (figures, panels, visuals, data, callbacks).

scene = dvz.scene(batch)

# ... your code here ...

# Run the application. The last argument is the number of frames (0 = infinite loop).

dvz.scene_run(scene, app, 0)

# App and scene clean up, memory freeing, etc.

dvz.scene_destroy(scene)

dvz.app_destroy(app)

Internally, the scene API generates a stream of Datoviz Intermediate Protocol (DIP) requests and sends them to the Datoviz Vulkan renderer (managed by the app). The DIP closely resembles the WebGPU specification. This decoupled architecture ensures that, in the future, the scene API can be implemented on top of other non-Vulkan DIP renderers (including a future JavaScript-based one).

Although the architecture is designed with multithreading in mind (allowing for data computation and transfers without blocking the event loop), our primary focus has been on single-threaded applications so far. Multithreading functionality will be provided and documented at a later time.

Figures¶

A Figure is a window on which to draw visuals.

It is created as follows:

# Create a figure with size 800 x 600 and no optional flags.

figure = dvz.figure(scene, 800, 600, 0)

Panels¶

A Panel is a rectangular portion of a Figure on which to render visuals.

You can create a default panel spanning the entire figure as follows:

panel = dvz.panel_default(figure)

Create an arbitrary panel as follows:

# x, y is the offset of the top left panel corner.

# w, h is the size in pixels of the panel.

panel = dvz.panel(figure, x, y, w, h)

Visuals¶

The Visual is the most important object type in Datoviz. It represents a visual collection of similar elements, such as points, markers, segments, glyphs (text), paths, images, meshes, and more.

The concept of a collection is crucial for high-performance rendering with GPUs. Visual elements of the same type should be grouped within the same Visual to optimize performance.

The primary limitation of grouping elements together is that they currently share the same transform, meaning they share the same coordinate system.

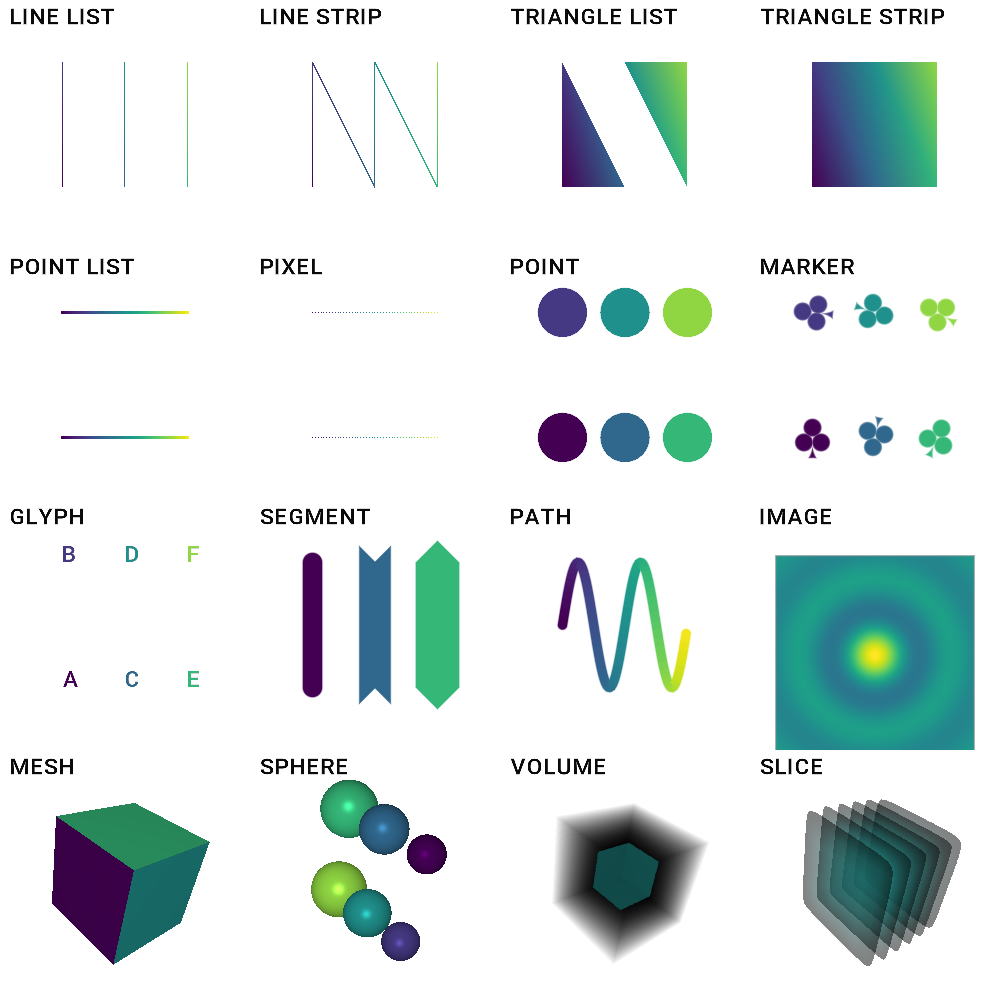

Datoviz offers a predefined set of common visuals:

- Basic visuals (faster but lower quality than other visuals):

basicwith an adequatedvz.PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_*enumeration, supporting pixels (POINT_LIST), aliased thin lines (LINE_LIST,LINE_STRIP), triangles (TRIANGLE_LIST,TRIANGLE_STRIP); - 0D visuals:

pixel,point(disc),marker,glyph(string characters rendered on the GPU with multichannel signed distance fields); - 1D visuals:

segment,path; - 2D visuals:

image; - 3D visuals:

mesh,sphere(2D sprites with "fake" 3D rendering, also known as impostors),volume(currently using a basic GPU raymarching algorithm),slice(volume image slices).

The visuals are implemented on the GPU using advanced antialiasing techniques within the shaders.

Additional visuals and the ability to create custom visuals via user-provided shaders will be added in the future.

To create a visual, use this:

# Create a `point` visual with no optional flags.

visual = dvz.point(batch, 0)

Visual data¶

Once a visual is created, you can specify its data using the provided visual-specific functions.

The most common types of visual properties are point positions and colors, but each visual has its own specific data properties (e.g., size, shape, groups). For more details, refer to the C API reference.

Text¶

Rendering high-quality text on the GPU efficiently is challenging. Several methods have been developed within the graphics community. Datoviz currently offers or plans to offer the following visuals:

glyph: Reasonably good quality, supports scaling, but currently not ideal for small font sizes. Utilizes multi-channel signed distance fields. Refer to Chlumsky's code.monoglyph: Fast but very low quality and still experimental (may not work on Linux for now). See glumpy's example.font: High quality but slow and does not support scaling. Renders on the CPU with freetype.vectorglyph: Potentially the most promising option, though not yet implemented! Refer to GreenLightning's code.

Datoviz currently includes the Roboto font and supports loading TTF/OTF fonts directly via freetype, which is a library dependency. Additional fonts may be integrated into Datoviz in the near future.

Additionally, we are exploring basic standalone LaTeX rendering in Datoviz, potentially using a micro LaTeX renderer such as MicroTeX. This approach would not require a LaTeX distribution on the client side and would be particularly useful for rendering mathematical equations.

This could work via bundling of the New Computer Modern font (NewCMMath-Regular.otf).

Terminology¶

We use the following terminology:

- item: A single visual element, such as a particular point, marker, or a single image within an

imagevisual. Each visual represents a collection of elements, so animagevisual may represent one or multiple images. - group: A consecutive sequence of items that share common properties. This concept is mostly used in the

pathvisual, where a group refers to an entire path, while an item refers to a point within that path. Thus, apathvisual contains a set of points (items) organized into one or multiple disjoint paths (groups). - vertex: A 3D point sent to the GPU, which is managed transparently by Datoviz. For example, a single image is represented by two triangles and six vertices. Datoviz automatically handles the triangulation, so you typically don't need to concern yourself with vertices.

- index: In the mesh visual, an index refers to the set of vertices. A mesh is primarily defined by (1) a set of 3D points (vertices), and (2) a set of index triplets (three indices) that define a triangular face.

A visual represents a collection of n items, indexed from 0 to n-1.

Python ctypes bindings¶

C visual data functions expect pointers to arrays of a specific type, such as an array of vec3 (three float32 values) for positions, or an array of cvec4 (four char, representing RGBA uint8 unsigned bytes) for colors.

Python ctypes bindings are auto-generated and expect a NumPy array when a C visual data function expects a pointer to an array of values. Currently, the ctypes bindings check the dtype, shape, and C-contiguity of the provided arrays.

Position¶

The position property specifies the 3D coordinates of visual points. Some visuals require the point positions in a specific format. For instance, segment positions are defined by the 3D coordinates of the start and end points of each segment. Image positions are currently defined by the 2D coordinates of the top left and bottom right corners, though this may change based on user feedback.

To set the positions of a visual, for example the point visual, use this:

# Define a (N, 3) NumPy array of float32 values (one row = one point).

# Note that the C function dvz_point_position() expects a vec3 array.

pos = np.random.normal(size=(n, 3), scale=.25).astype(np.float32)

# Set the positions of `n` items starting with item #0.

# The last argument represents the optional data transfer flags (typically 0).

dvz.point_position(visual, 0, n, pos, 0)

- x: left to right

[-1, +1] - y: bottom to top

[-1, +1] - z: front to back

[-1, +1]

Positions must be provided in a normalized coordinate system, known as normalized device coordinates (NDC) in computer graphics terminology. Since your data is typically not in this range, you'll need to manually normalize it to the [-1, +1] interval before passing it to Datoviz.

Datoviz v0.2 does not yet include built-in axes or data normalization features, but these will be introduced in v0.3.

Color¶

Colors are passed as RGBA values, each represented by four uint8 values. Use opacity values less than 255 in the last component (the alpha channel, a) to create transparent elements.

Textures¶

Textures are used in the image (2D textures), mesh (2D textures), and volume (3D textures) visuals. Refer to the examples for more details.

For example, here’s how to create a 2D texture and apply it to an image visual:

# Assuming rgba is a 3D NumPy array (height, width, 4).

# NOTE: the dtype of the NumPy array should match the Vulkan format below.

# NOTE: Datoviz expects row-major order for arrays (C order)

# TODO: write a NumPy-Vulkan/Datoviz format correspondance table in the documentation.

# TODO: write a utility function automatically mapping NumPy dtypes to Vulkan/Datoviz formats.

height, width = rgba.shape[:2]

# Texture parameters.

format = dvz.FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_UNORM # This Vulkan format corresponds to 4*uint8 values.

address_mode = dvz.SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_CLAMP_TO_BORDER # Texture address mode.

filter = dvz.FILTER_LINEAR # Linear filtering, use dvz.FILTER_NEAREST to disable.

# Create a texture out of a RGB image.

# NOTE: since dvz_tex_image() accepts any type of pointer, we need to manually convert the NumPy

# array to a void* pointer. This is done with the `A_()` function (`from datoviz import A_`).

tex = dvz.tex_image(batch, format, width, height, A_(rgb))

# Finally, we assign this texture to the image visual.

dvz.image_texture(visual, tex, filter, address_mode)

Data sharing¶

Since textures are decoupled from visuals, they can be easily shared across different visuals.

However, it is not yet straightforward to share other types of data between visuals. While the underlying architecture is designed to support this, the user-facing API does not currently offer this capability.

Dynamic data updates¶

You can modify the data of a visual dynamically while the event loop is running, such as in an event callback.

After updating a visual, the function dvz.visual_update(visual) is automatically called internally to trigger the data updates on the GPU, so you should not need to call it manually in most cases.

Shapes¶

The mesh visual can be directly used with properties such as vertices, indices, colors, normals, and texture coordinates. Alternatively, you can use the Shape structure, which encapsulates these arrays. Shapes can be created using functions for predefined forms, along with affine transforms, merging, and other operations.

Interactivity¶

Two types of interactivity patterns are currently supported:

- Panzoom (2D): Pan with left mouse drag, zoom with right mouse drag.

- Arcball (3D): Rotate with left mouse drag.

Additional interactivity patterns will be implemented in the future.

To define the interactivity pattern in a panel:

pz = dvz.panel_panzoom(panel)

# or

arcball = dvz.panel_arcball(panel)

Refer to the C API reference for functions you can use to manually control the panzoom or arcball. After updating these interactivity objects, you need to update the panel to apply your changes:

dvz.panel_update(panel)

Event callbacks¶

You can define custom event callbacks to respond to mouse and keyboard interactions, as well as set up timers.

Mouse¶

Define a mouse callback as follows:

@dvz.mouse

def on_mouse(app, window_id, ev):

# Access the mouse event structure.

# Mouse position.

x, y = ev.pos

print(f"Position {x:.0f},{y:.0f}")

# Detect mouse event type.

if ev.type == dvz.MOUSE_EVENT_CLICK:

# Identify mouse click button.

button = ev.content.b.button

print(f"Clicked with button {button}")

The mouse event types are:

MOUSE_EVENT_RELEASE b DvzMouseButtonEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_PRESS b DvzMouseButtonEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_MOVE

MOUSE_EVENT_CLICK c DvzMouseClickEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_DOUBLE_CLICK c DvzMouseClickEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_DRAG_START d DvzMouseDragEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_DRAG d DvzMouseDragEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_DRAG_STOP d DvzMouseDragEvent

MOUSE_EVENT_WHEEL w DvzMouseWheelEvent

Use the corresponding letter after ev.content., such as ev.content.b for a DvzMouseButtonEvent structure. Refer to the C API reference for more details about the fields in these structures.

The mouse buttons are:

MOUSE_BUTTON_LEFT = 1

MOUSE_BUTTON_MIDDLE = 2

MOUSE_BUTTON_RIGHT = 3

Datoviz currently does not provide built-in picking functionality. The only information available in mouse event callbacks is the pixel coordinates of the mouse cursor.

Keyboard¶

Define a keyboard callback as follows:

# Keyboard event callback function.

@dvz.keyboard

def on_keyboard(app, window_id, ev):

# Get the key code (refer to the C API reference).

key = ev.key

# Determine modifier flags.

mods = {

'shift': ev.mods & dvz.KEY_MODIFIER_SHIFT != 0,

'control': ev.mods & dvz.KEY_MODIFIER_CONTROL != 0,

'alt': ev.mods & dvz.KEY_MODIFIER_ALT != 0,

'sup': ev.mods & dvz.KEY_MODIFIER_SUPER != 0,

}

mods = '+'.join(key for key, val in mods.items() if val)

# Identify the keyboard event type (PRESS, RELEASE, REPEAT).

type = {

dvz.KEYBOARD_EVENT_PRESS: 'press',

dvz.KEYBOARD_EVENT_REPEAT: 'repeat',

dvz.KEYBOARD_EVENT_RELEASE: 'release',

}

type = type.get(ev.type, '')

print(f"{type} {mods} {key}")

# Register the keyboard callback function.

dvz.app_onkeyboard(app, on_keyboard, None)

Timer¶

Define a timer as follows:

# Timer callback.

@dvz.timer

def on_timer(app, window_id, ev):

# Use the timer index for identifying multiple timers.

idx = ev.timer_idx

step = ev.step_idx

time = ev.time

print(f"{time:.3f}: timer #{idx}, step {step}")

# Set the timer frequency.

frequency = 4

# Define a timer with this frequency, starting after 0.5 seconds, stopping after 50 ticks.

# Use 0 as the last argument for an infinite timer.

dvz.app_timer(app, 0.5, 1. / frequency, 50)

# Register the timer callback.

dvz.app_ontimer(app, on_timer, None)

Manual 3D camera control¶

By default, a panel is 2D. To define a 3D panel, you can either use an arcball (see above) or a generic 3D perspective camera. Here's how to define a 3D perspective camera:

from datoviz import vec3

# Define a 3D perspective camera.

camera = dvz.panel_camera(panel)

# Set the camera position.

dvz.camera_position(camera, vec3(x, y, z))

# Set the position of the point the camera is looking at.

dvz.camera_lookat(camera, vec3(lx, ly, lz))

You can implement custom 3D camera control by calling these functions within mouse and keyboard callbacks. After these camera functions are called, it is crucial to apply the changes to the panel:

dvz.panel_update(panel)

Graphical User Interfaces¶

Datoviz includes basic GUI capabilities via the Dear ImGui C++ library. A future version of Datoviz may allow more direct use of Dear ImGui functionalities beyond the current wrappers.

To display a GUI dialog, follow these steps:

- Use the

dvz.CANVAS_FLAGS_IMGUIflag when creating a figure (last argument ofdvz.figure()). - Define a GUI callback function.

- Register the GUI callback function.

Example:

from datoviz import vec2, S_

@dvz.gui

def on_gui(app, fid, ev):

"""GUI callback function."""

# Set the size of the next GUI dialog.

dvz.gui_size(vec2(200, 100))

# Start a GUI dialog with a title.

# Use `S_()` to pass a Python string to a C function expecting a const char*.

dvz.gui_begin(S_("My GUI dialog"), 0)

# Display a button.

clicked = dvz.gui_button(S_("Click me"), 150, 30)

if clicked:

print("Clicked!")

# End the GUI dialog.

dvz.gui_end()

# Associate a GUI callback function with a figure.

dvz.app_gui(app, dvz.figure_id(figure), on_gui, None)

The GUI callback function is called on every frame. To avoid blocking the main event loop, ensure there is no long-lasting computation within it. Dear ImGui recreates the entire GUI at each frame (immediate mode rendering). GUI widget functions like dvz.gui_button() typically return a boolean indicating whether the widget's state has changed.

Using Datoviz in a C/C++ application¶

This section provides general instructions for C/C++ developers who want to use Datoviz in their library or application.

Ubuntu¶

Note: to be completed.

Install the .deb package and look at the .c examples in examples/.

macOS (arm64)¶

Looking at the justfile (pkg and testpkg commands) may be helpful.

To build an application using Datoviz:

- You need to link your application to

libdatoviz.dylib, that you can build yourself or find in the provided.pkginstallation file. - You also need to link to the non-system dependencies of Datoviz, for now they are

libvulkan,libshaderc_shared,libMoltenVK("emulating" Vulkan on top of Apple Metal),libpngandfreetype. You can see the dependencies withjust deps(which usesotoolonlibdatoviz.dylib). You'll find these dependencies inlibs/vulkan/macosin the GitHub repository. - You should bundle these

dylibdependencies alongside your application, and that will depend on how your application is built and distributed. - Note that the

just pkgscript modifies the rpath oflibdatoviz.dylibwithinstall_name_toolbefore building the.pkgpackage to declare that its dependencies are to be found in the same directory. - Another thing to keep in mind is that, for now, the

VK_DRIVER_FILESenvironment variable needs to be set to the absolute path tolibs/vulkan/macos/MoltenVK_icd.json(available in this GitHub repository). The.pkgpackage installs it to/usr/local/lib/datoviz/MoltenVK_icd.json. Right now,datoviz.hautomatically sets this environment variable if it's included in the source file implementing yourmain()entry-point. These complications are necessary to avoid requiring the end-users to install the Vulkan SDK manually.

Windows¶

To be completed.

Technical notes for C/C++ developers¶

- 🧠 Memory management. Datoviz uses opaque pointers and manages its own memory. Porting the relatively light high-level code of Datoviz (scene API) to a more modern and safer language may be considered in the future.

- 💻 C/C++ usage. Datoviz employs a restricted and straightforward usage of C, with very limited C++ functionality (mostly common dynamic data structures, in ~10% of the code).

- 📂 Data copies. When passing data to visuals, data is copied by default to Datoviz for memory safety reasons. This might impact performance and memory usage when handling large datasets (tens of millions of points). We will soon document how to avoid these extra copies and prevent crashes related to Datoviz accessing deallocated memory.

- 🏗️ Modular architecture. Datoviz v0.2+ features a modular architecture where the low-level Vulkan-specific rendering engine is decoupled from the higher-level visual and interactive logic. A private asynchronous message-based protocol is used internally, enabling a future Javascript/WebAssembly/WebGPU port of Datoviz, which we plan to work on in the coming years.

- 👥 Contributing. This modular architecture allows C/C++ contributors without GPU knowledge to propose improvements and new functionality in the higher-level parts.

- 🔗 Bindings. While we provide raw ctypes bindings in Python to the Datoviz C API, our goal is to implement as much functionality in C/C++ to offer the same functionality to other languages that may provide Datoviz bindings in the future (Julia, Rust, R, MATLAB...).